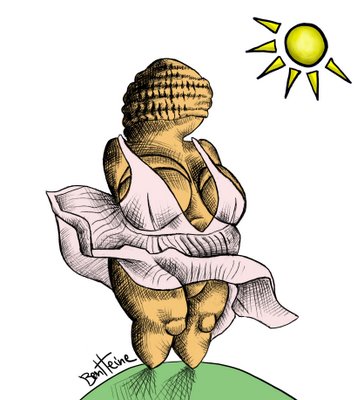

Marilyn Willendorf

.

Woman from Willendorf

By Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe

Nowadays, in the captions to illustrations of her in books, the word "Woman" is sometimes substituted for "Venus," a switch that has contributed, together with the current growing sensitivity to the visual representation of women, to a shift in how she is perceived.

One effect of this name change is to remove her from immediate identification as a goddess and to think of her in more mundane, human terms. This demystification, allows us to approach the figure more on its own terms and, without the encumbering preconceptions provoked by a name, gives us a better chance of interpreting its meaning.

The sculpture shows a woman with a large stomach that overhangs but does not hide her pubic area. A roll of fat extends around her middle, joining with large but rather flat buttocks. She is not, as Luce Passemard has pointed out, steatopygous (that is, possessing protruding buttocks). Piette had been the first to use the term steatopygous to describe the "Venus" figurines, regarding it as a racial feature that he related to the appearance of women in African tribes such as the Bushmen, Pygmies and Hottentots (KhoiKhoi). The implication that Aurignacian people may have been African in appearance influenced subsequent interpretations.

Her thighs are also large and pressed together down to the knees. Her forearms, however, are thin, and are shown draped over and holding, with cursorily indicated fingers, the upper part of her large breasts. Small markings on her wrists seem to indicate the presence of bracelets. Her breasts are full and appear soft, but they are not sagging and pendulous. The nipples are not indicated.

Her genital area would appear to have been deliberately emphasized with the labia of the vulva carefully detailed and made clearly visible, perhaps unnaturally so, and as if she had no pubic hair. This, combined with her large breasts and the roundness of her stomach, suggests that the "subject" of the sculpture is female procreativity and nurture and the piece has long been identified as some sort of fertility idol.

A characteristic of all the Paleolithic "Venus" figurines exhibited by the Willendorf statuette is the lack of a face, which for some, arguing that the face is a key feature in human identity, means that she is to be regarded as an anonymous sexual object rather than a person; it is her physical body and what it represents that is important.

From the front, the place where her face should be seems to be largely concealed by what are generally described as rows of plaited hair wrapped around her head.

Close examination, however, reveals that the rows are not one continuous spiral but are, in fact, composed in seven concentric horizontal bands that encircle the head, with two more half-bands below at the back of her neck. The topmost circle has the form of a rosette. The bands vary in width from front to back to sides, and also vary in size from each other. Cut across the groove separating each band at regular, closely-spaced intervals is a series of more or less lozenge-shaped deep vertical notches, some wide, others narrow, that extend equally into the band above and into the band below. These notches alternate between bands to produce the effect of braided or plaited hair. That it is intended to be understood as braided hair seems clear, although it has been suggested recently that the figure is in fact wearing a fiber-based woven hat or cap.

When seen in profile, the impression is that the figure is looking down with her chin sunk to her chest, and her hair looks more like hair; longer at back and falling and gathering like real hair might on her upper back. Some find it significant that the number of full circles is seven; many thousands of years later seven was regarded as a magic number.

Such elaborate treatment of hair is extremely rare in Paleolithic figurines, and the considerable attention paid to it by the sculptor must mean it had some significance. In later cultures, hair has been considered a source of strength, and as the seat of the soul.

Hair also has a long history as a source of erotic attraction that lies, perhaps surprisingly, not so much in its color, style, or length, but in its odor. The erotic attraction of the odor of hair is obviously rooted in the sense of smell, which plays a considerable role in sexual relations. Though greatly diminished in the modern world, smell was paramount in establishing an erotic rapport with a mate, as it still is among animals. In this context, the hair of the woman or goddess represented in the "Venus" of Willendorf figurine may have been regarded as erotically charged as her breasts and pubic area.

Another characteristic of Paleolithic "Venus" figurines is the lack of feet. In the archaeological report of her finding, the Willendorf statuette is described as perfectly preserved in all its parts, so it appears she never had feet.

It has been suggested that possibly the intention was to curtail the figurine's power to leave wherever she had been placed.

A more common explanation is that because the statuette served as a fertility idol, the sculptor included only those parts of the female body needed for the conception and nurture of children. Even if she had feet, though, it seems unlikely that she was meant to stand up. This is even more true of the other Paleolithic figurines.

Nor it seems was she ever intended to lie in a supine position. In fact, her most satisfactory, and most satisfying, position is being held in the palm of the hand. When seen under these conditions, she is utterly transformed as a piece of sculpture. As fingers are imagined gripping her rounded adipose masses, she becomes a remarkably sensuous object, her flesh seemingly soft and yielding to the touch.

What her identity and purpose may have been, why and for what reason she was carved, becomes an even more pressing question. If we dismiss all associations with goddesses and fertility figures, and assume an objective response to what we see, she might be identified as simply a Stone-Age doll for a child.

But this strikes us as unsatisfactory, not the least because of the very high degree of artistic ability exhibited in the sculpting of her forms. Compared with the other Paleolithic figurines in this group, the "Venus" of Willendorf is a remarkably realistic representation of a fat woman.

This analysis appeared on http://witcombe.sbc.edu

By the same author, see :

- Mother Goddess

- Women in the Stone Age

- What is in a name?